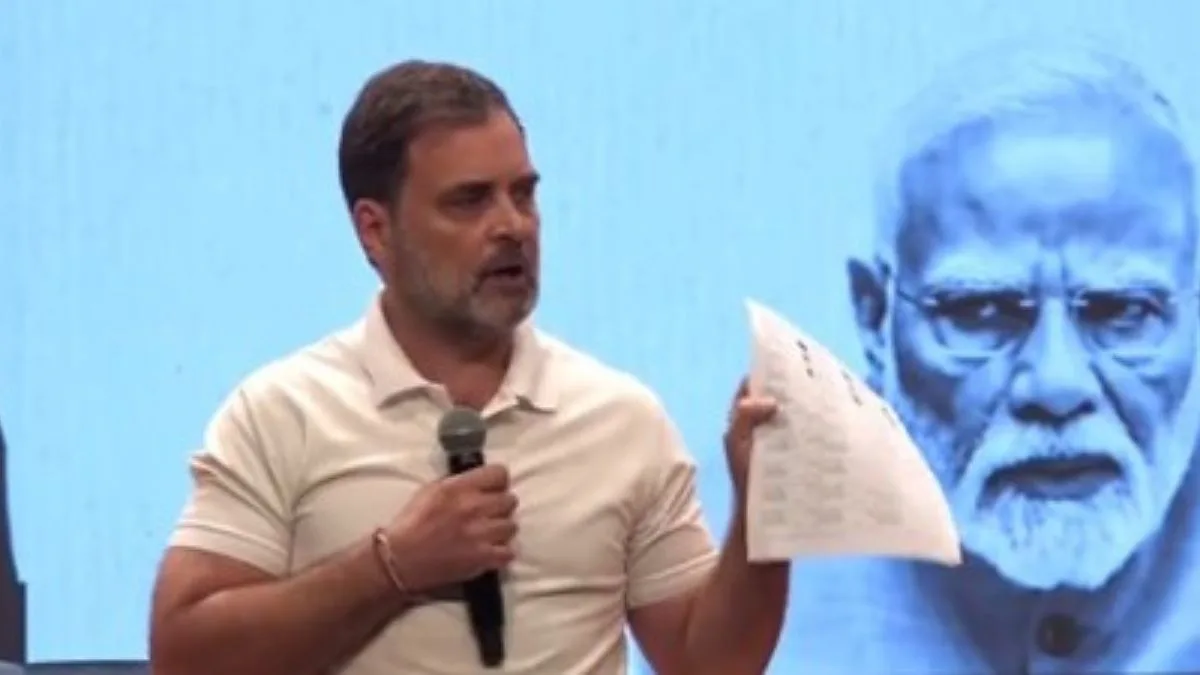

In the high-stakes arena of Indian politics, where democracy’s very foundations are constantly tested, Rahul Gandhi’s recent “hydrogen bomb” revelation has sparked one of the sharpest debates in recent memory. On September 18, 2025, during a special press conference in New Delhi, the Congress leader accused the Election Commission of India (ECI) of enabling a “centralized criminal setup” that systematically deletes voters—particularly those from marginalized communities such as minorities, Dalits, and opposition supporters.

Gandhi highlighted the case of Aland constituency in Karnataka, where 6,018 fraudulent voter deletion applications were filed using centralized software and out-of-state mobile numbers. He claimed this was not an isolated incident but evidence of a “blueprint for vote chori” (vote theft) fueled by unchecked centralization.

The controversy doesn’t just raise questions about electoral integrity—it revives a larger, timeless debate: centralized vs. decentralized systems.

Centralized Systems: Efficiency, but with a Dangerous Weakness

Centralized systems consolidate authority, data, and decision-making into a single hub. In elections, this means the ECI manages voter rolls, deletions, and verifications through one streamlined mechanism.

Strengths of centralization include:

- Uniform standards across states

- Faster national-level updates

- Cost-effective aggregation of data

For example, during Bihar’s Special Intensive Revision (SIR) in 2025, the ECI deleted over 6.5 million names from draft rolls, citing deaths, duplicates, and migrations. On paper, this was a demonstration of efficiency: centralized algorithms flagged anomalies, and booth-level officers conducted door-to-door verifications.

But Gandhi’s allegations expose the flip side of centralization—its single point of failure. In Aland, thousands of voters were allegedly disenfranchised through fraudulent deletions, executed at scale without local checks. Centralized systems can be extremely vulnerable to manipulation if the central authority—or the software powering it—is compromised.

| Aspect | Centralized Systems (e.g., ECI Voter Management) |

|---|---|

| Strengths | Consistency; speed; cost efficiency |

| Weaknesses | Top-down opacity; prone to abuse; weak local oversight |

| Real-World Risk | Alleged bulk voter deletions in Karnataka (6,018 cases) |

Globally, this isn’t unique to India. Centralized financial databases have fallen victim to hacks, while centralized electoral systems in authoritarian states often facilitate large-scale fraud.

Decentralized Systems: Power Through Distribution

Decentralization spreads authority across multiple nodes—states, districts, or even local communities—reducing reliance on one central point of control.

Strengths of decentralization include:

- Local accountability

- Greater transparency

- Resilience against mass tampering

Imagine an election system where voter deletions required multi-level approvals: local booth-level officers, community hearings, and state election bodies all had to validate before names could be removed. Fraudulent applications from outside a constituency, like in Aland, would trigger immediate local alerts instead of slipping through unchecked software.

| Aspect | Decentralized Systems (Hypothetical Reform) |

|---|---|

| Strengths | Tamper-resistant; inclusive; locally accountable |

| Weaknesses | Slower processes; possible inconsistencies; higher costs |

| Real-World Benefit | Could have prevented Bihar’s mass deletions by ensuring multi-node approvals |

Examples abroad strengthen this argument. Switzerland distributes electoral power across cantons, limiting federal overreach. Estonia’s e-voting system uses decentralized verification processes to resist tampering.

Rahul Gandhi’s “Hydrogen Bomb”: A Wake-Up Call

Rahul Gandhi’s remarks weren’t just political theater. He accused Chief Election Commissioner Gyanesh Kumar of “protecting murderers of democracy” and demanded the release of technical data within a week. The BJP dismissed his claims as “irresponsible,” yet public trust in the ECI appears shaken—especially after years of controversies over Aadhaar-linked deletions and alleged voter suppression.

Whether or not one accepts Gandhi’s “hydrogen bomb” metaphor, the scandal underlines a clear risk: when control over elections is overly centralized, democracy itself becomes fragile.

The Way Forward: A Hybrid Approach

India doesn’t have to choose between efficiency and accountability. The path forward could be a hybrid model:

- Centralized national databases for consistency and scale

- Decentralized safeguards like local verification, blockchain-backed voter rolls, and independent oversight panels

- Mandatory transparency in publishing deletion data to ensure accountability

Ultimately, the debate is bigger than Rahul Gandhi’s accusations or even the ECI. It’s about the architecture of power in India’s democracy. Centralized systems may streamline governance, but without decentralized checks, they risk becoming tools of disenfranchisement.

As Gandhi warned, unchecked centralization could mean votes are “stolen”—and with them, the very voice of the people. If India wants to defuse its democratic time bombs, it must strike a balance between efficiency and fairness.

✅ Key Takeaway: Centralized systems deliver speed and uniformity but create vulnerabilities to abuse. Decentralized systems, though slower, provide resilience and accountability. India’s electoral future may depend on blending the two—before the next “hydrogen bomb” shakes democracy again.